Amplifying

Eds. Setareh Noorani, Tabea Nixdorff

208 p, ills bw, 16 × 23,7 cm, Dutch/English

Published June 2024

ISBN 978-90-834194-2-8

Available for €18 via your local bookstore

The book Amplifying brings together written manifestations that trace the beginnings of Black feminism in the Netherlands. Amplifying means giving credit to, mentioning, over and over, and supporting the circulation of sources and authors that are formative for our thinking and practices. It also means putting in the “extra effort” to seek out voices that are not immediately within reach as their recognition has been compromised by structural forces of oppression. In the early 1980s, the political term “black” (“zwart” in Dutch) was introduced in the Netherlands to build alliances between women from different diasporic communities, who were faced with racism in their everyday lives.

Archival materials featured in this book include the original manuscript of the essay Survivors: Portrait of the Group Sister Outsider (1986), written by Gloria Wekker in collaboration with the Black lesbian literary collective Sister Outsider, the seminal speech Statement of the Black Women’s Group (1983) by Julia da Lima, a contextualizing interview with Tineke E. Jansen and Mo Salomon (1984), excerpts from the book launch of Philomena Essed’s Everyday Racism (1984), and ephemera authored by other Black feminist groups in the Netherlands, such as Zwarte Vrouwen & Racisme, Flamboyant, Ashanti, and Groep Zwarte Vrouwen Nijmegen.

These materials were researched at the collection of the International Archive for the Women’s Movement (IAV) at Atria, Institute on Gender Equality and Women’s History in Amsterdam. They are framed by an introductory essay by Setareh Noorani and Tabea Nixdorff as well as an intergenerational roundtable conversation. Translations into English and Dutch (the roundtable conversations were held as a multilingual space) are provided by Jenny Mijnhijmer, Tirsa With, Canan Marasligil and Shira Wolfe.

- Book Cover Amplifying, eds. Setareh Noorani, Tabea Nixdorff, published by Archival Textures, 2024.

- Telegram Gefeliciteerd [Congratulations] from the Lesbisch Archief Leeuwarden to the collective Sister Outsider and Feministische Uitgeverij Sara, on the occasion of the publication of “Zami” by Audre Lorde in Dutch, 1985.

- Flyer Vrouwenboekwinkel Xantippe: Audre Lorde signeert [Xantippe Women’s Bookstore: Audre Lorde Book Signing], 1986.

- Typewritten manuscript (excerpt) for the interview Alleen in de derde wereld wonen zwarte vrouwen. Het witte karakter van de WUV [Black Women Only Live in the Third World: The White Character of the WUV] with Mo (formerly Moniek) Salomon and Tineke E. Jansen, edited by Mavis Carrilho and Judith Vega, Amsterdam, 1984.

Source of images 2-4: Collection of the International Archive for the Women’s Movement (IAV), at Atria, Institute on Gender Equality and Women’s History, Amsterdam; featured in the book Amplifying.

Red. Setareh Noorani, Tabea Nixdorff

208 p, ills zw, 16 × 23,7 cm, Nederlands/Engels

Verschenen in juni 2024

ISBN 978-90-834194-2-8

Voor €18 te koop in jouw lokale boekenwinkel

Het boek Amplifying (‘Stemmen versterken’ in het Nederlands) verzamelt geschreven uitingen die de beginselen van Zwart feminisme in Nederland volgen. Met stemmen versterken bedoelen we erkenning geven, keer op keer benoemen, en het ondersteunen van het verspreiden van bronnen en auteurs die bepalend zijn geweest voor onze gedachten en ons werk. Het betekent ook ‘extra moeite doen’ om stemmen te vinden die niet onmiddellijk binnen handbereik liggen, omdat hun erkenning door structurele krachten van onderdrukking is aangetast. In de vroege jaren 80 werd de politieke term ‘zwart’ in Nederland geïntroduceerd om bondgenootschappen tussen vrouwen uit verschillende diasporagemeenschappen, die in hun alledaagse leven geconfronteerd werden met racisme, op te bouwen.

Het archiefmateriaal in dit boek omvat onder andere het originele manuscript van het essay Overlevers: Groepsportret van Sister Outsider (1986), geschreven door Gloria Wekker in samenwerking met het Zwarte lesbische literaire collectief Sister Outsider, de baanbrekende toespraak Verklaring van de Zwarte Vrouwengroep (1983) door Julia da Lima, een interview met Tineke E. Jansen en Mo Salomon (1984) dat context geeft, fragmenten van de boekenlancering van Philomena Esseds Alledaags Racisme (1984), en uitgaven geschreven door andere Zwarte feministische groepen in Nederland, zoals Zwarte Vrouwen & Racisme, Flamboyant, Ashanti, en Groep Zwarte Vrouwen Nijmegen.

Dit materiaal is onderzocht in de collectie van het Internationaal Archief voor de Vrouwenbeweging (IAV) in Atria, kennisinstituut voor emancipatie en vrouwengeschiedenis in Amsterdam. Het wordt gepositioneerd door een inleidend essay geschreven door Setareh Noorani en Tabea Nixdorff, en door een intergenerationeel rondetafelgesprek. De vertalingen naar het Engels en Nederlands (de rondetafelgesprekken waren meertalig) zijn door Jenny Mijnhijmer, Tirsa With, Canan Marasligil en Shira Wolfe.

- Boekomslag Amplifying, red. Setareh Noorani, Tabea Nixdorff, gepubliceerd door Archival Textures, 2024.

- Telegram Gefeliciteerd door Lesbisch Archief Leeuwarden naar het collectief Sister Outsider en Feministische Uitgeverij Sara, ter gelegenheid van de publicatie van “Zami” door Audre Lorde in het Nederlands, 1985.

- Flyer Vrouwenboekwinkel Xantippe: Audre Lorde signeert, 1986.

- Getypt manuscript (uittreksel) voor het interview Alleen in de derde wereld wonen zwarte vrouwen. Het witte karakter van de WUV met Mo (vroeger Moniek) Salomon en Tineke E. Jansen, onder redactie van Mavis Carrilho and Judith Vega, Amsterdam, 1984.

Bron van afbeeldingen 2-4: Collectie van het Internationaal Archief voor de Vrouwenbeweging (IAV) in Atria, kennisinstituut voor emancipatie en vrouwengeschiedenis, Amsterdam; gepubliceerd in het boek Amplifying.

(Re)claiming

Eds. Noah Littel, Tabea Nixdorff

184 p, ills color & bw, 16 × 23,7 cm, Dutch/English

Published June 2024

ISBN 978-90-834194-3-5

Available for €18 via your local bookstore

The book (Re)claiming presents ways in which various queer and feminist communities and initiatives in the Netherlands have (re)claimed the triangle—along with other symbols, words and stories—and in doing so take up an empowering position in a hostile society. (Re)claiming can mean both a proud identification with, and protest against the stigmatization for which a symbol, word, gesture or story was designed.

Besides a collection of buttons, archival materials featured in this book include short statements and flyers by queer groups such as SUHO, Sjalhomo, Roze Front, Roze Driehoek, Roze Gebaar, Van Doofpot tot Mankepoot, Interpot/ILIS, Lesbisch Archief Amsterdam, Strange Fruit Vrouwen and Groep Zwarte Vrouwen Nijmegen, as well as a text by Karin Daan, the designer of the Homomonument in Amsterdam. With this selection, this book brings together queer, trans, crip, feminist, Jewish and Black perspectives on (re)claiming as an activist strategy.

Most of these materials were researched at IHLIA LGBTI Heritage in Amsterdam, with additions found at the International Institute of Social History and the International Archive for the Women’s Movement (IAV-Atria) in Amsterdam, and LAN Lesbisch Archief Nijmegen. The materials are framed by an introductory essay by Noah Littel as well as an intergenerational roundtable conversation. Translations into English and Dutch (the roundtable conversations were held as a multilingual space) are provided by Canan Marasligil and Shira Wolfe.

- Book cover (Re)claiming, eds. Noah Littel, Tabea Nixdorff, published by Archival Textures, 2024.

- Magazine cover De Verkeerde K(r)ant. Flikkers vecht terug! [The Wrong Side/Paper. Fags fight back!] by Roze Driehoek, no. 7, Eindhoven, 1981.

- Magazine articles “Zo, en hoe zit het nu met Nijmegen?" [So, what about the dykes…?] and “Potten en flikkers aller landen…” [Dykes and Fags of All Countries…] in Informatiebulletin ter gelegenheid van de internationale potten- en flikkerdag, edited by Liesbeth Jansen, Pieter Lamberts, published by Het Roze Front, Nijmegen, 1984.

- Information flyer Zit Roze Gebaar nog in de kast!?! [Is Pink Sign Language still Closeted?] by Roze Gebaar, distributed during the Symposium January 26, 1996 at the COC Amsterdam.

Source of images 2-4: Collection of IHLIA LGBTI Heritage, at Public Library OBA Oosterdok, Amsterdam; featured in the book (Re)claiming.

Red. Noah Littel, Tabea Nixdorff

184 p, ills kleur & zw, 16 × 23,7 cm, Nederlands/Engels

Verschenen in juni 2024

ISBN 978-90-834194-3-5

Voor €18 te koop in jouw lokale boekenwinkel

Het boek (Re)claiming (‘(terug)claimen’ in het Nederlands) presenteert manieren waarop verschillende queer en feministische gemeenschappen en initiatieven in Nederland de driehoek — en andere symbolen, woorden en verhalen — hebben (terug)geclaimd, en daarmee een empowerende positie in een vijandige maatschappij innemen. (Terug)claimen kan zowel een trotse identificatie met een symbool, woord, gebaar of verhaal betekenen, als ook een protest tegen de stigmatisering waarvoor het in eerste instantie bedoeld was.

Naast een verzameling buttons omvat het archiefmateriaal in dit boek korte statements en flyers van queer groepen zoals SUHO, Sjalhomo, Roze Front, Roze Driehoek, Roze Gebaar, Van Doofpot tot Mankepoot, Interpot/ILIS, Lesbisch Archief Amsterdam, Strange Fruit Vrouwen, en Groep Zwarte Vrouwen Nijmegen, en ook nog een tekst van Karin Daan, de ontwerper van het Homomonument in Amsterdam. Met deze selectie verzamelt dit boek queer, trans, crip, feministische, Joodse en Zwarte perspectieven over (terug)claimen als activistische strategie.

Het grootste gedeelte van dit materiaal werd onderzocht in IHLIA LGBTI Heritage in Amsterdam, met wat aanvullingen die gevonden werden in het Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis en het Internationaal Archief voor de Vrouwenbeweging (IAV-Atria) in Amsterdam, en LAN Lesbisch Archief Nijmegen. Het materiaal wordt gepositioneerd door een inleidend essay geschreven door Noah Littel, en door een intergenerationeel rondetafelgesprek. De vertalingen naar het Engels en Nederlands zijn door Canan Marasligil en Shira Wolfe.

- Bookomslag (Re)claiming, red. Noah Littel, Tabea Nixdorff, gepubliceerd door Archival Textures, 2024.

- Omslag van De Verkeerde K(r)ant. Flikkers vecht terug! door Roze Driehoek, no. 7, Eindhoven, 1981.

- Magazine articles “Zo, en hoe zit het nu met Nijmegen?" [So, what about the dykes…?] and “Potten en flikkers aller landen…” [Dykes and Fags of All Countries…] in Informatiebulletin ter gelegenheid van de internationale potten- en flikkerdag, edited by Liesbeth Jansen, Pieter Lamberts, published by Het Roze Front, Nijmegen, 1984.

- Informatie flyer Zit Roze Gebaar nog in de kast!?! door Roze Gebaar, gedistribueerd tijdens het symposium 26 januari 1996 in het COC Amsterdam.

Bron van afbeeldingen 2-4: Collectie IHLIA LGBTI Heritage, Openbare Bibliotheek Amsterdam Oosterdok, Amsterdam; hergepubliceerd in het book (Re)claiming.

Posting

Eds. Carolina Valente Pinto, Tabea Nixdorff

144 p, ills color, 16 × 23,7 cm, Dutch/English

Published June 2024

ISBN 97890-834194-4-2

Available for €18 via your local bookstore

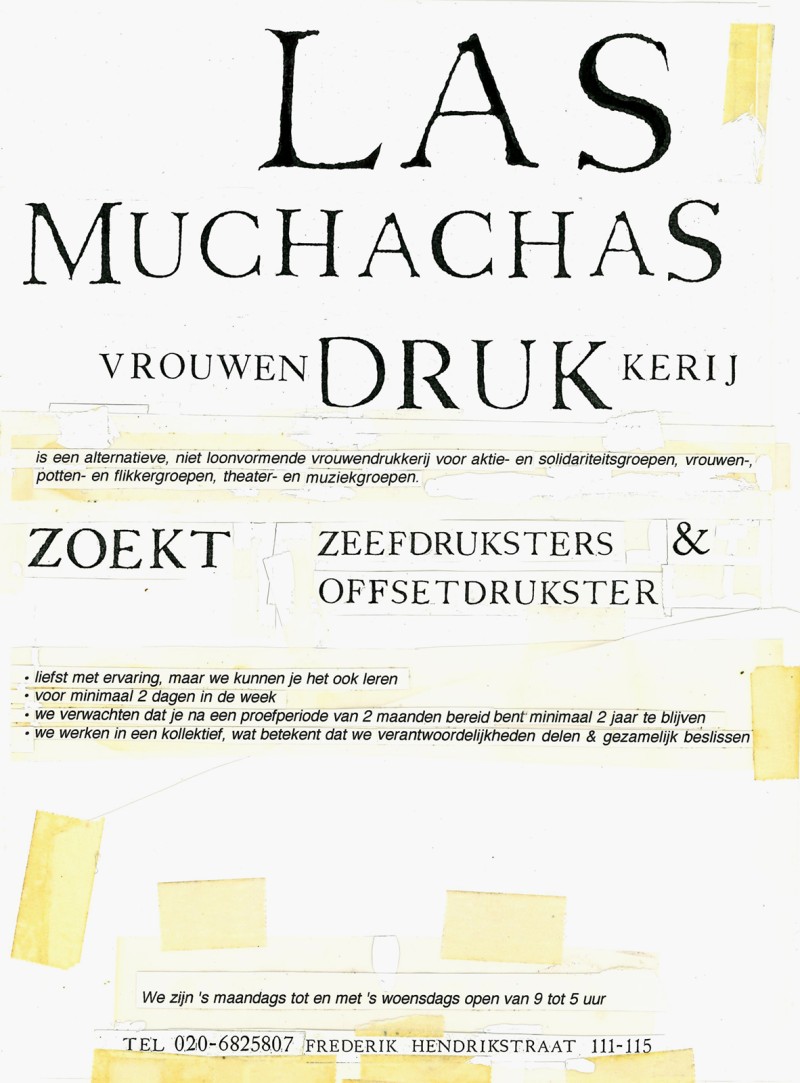

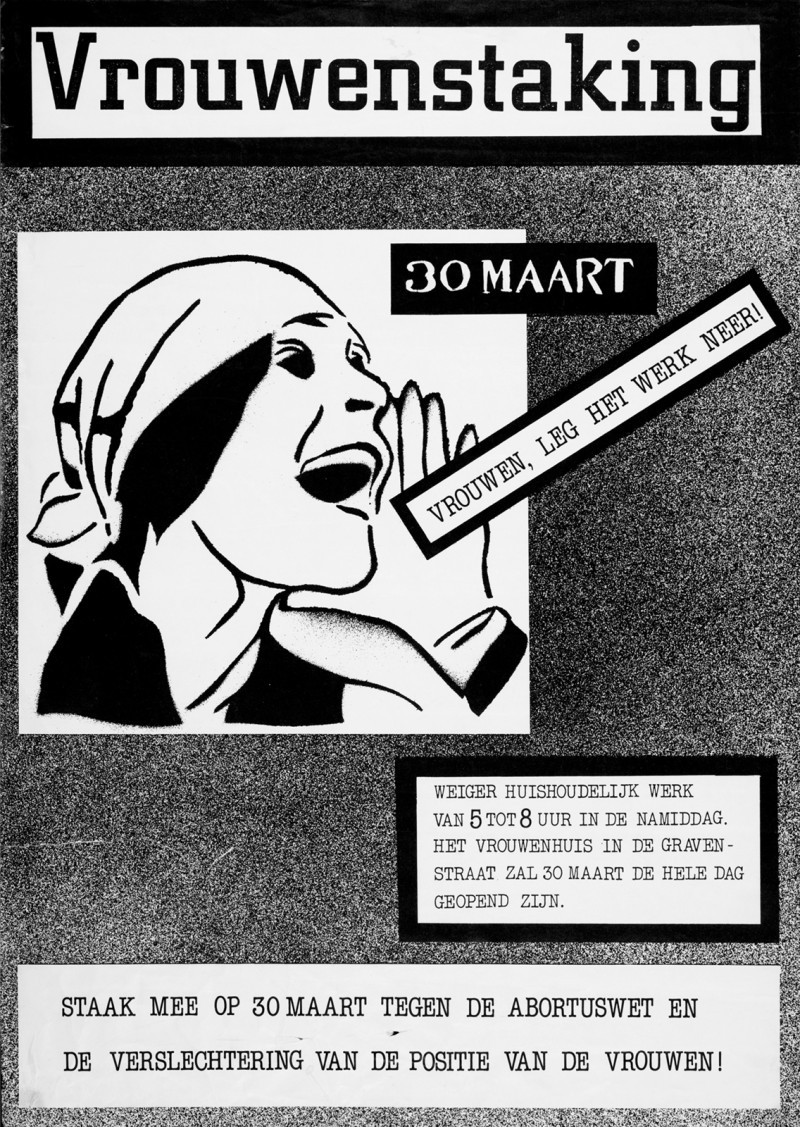

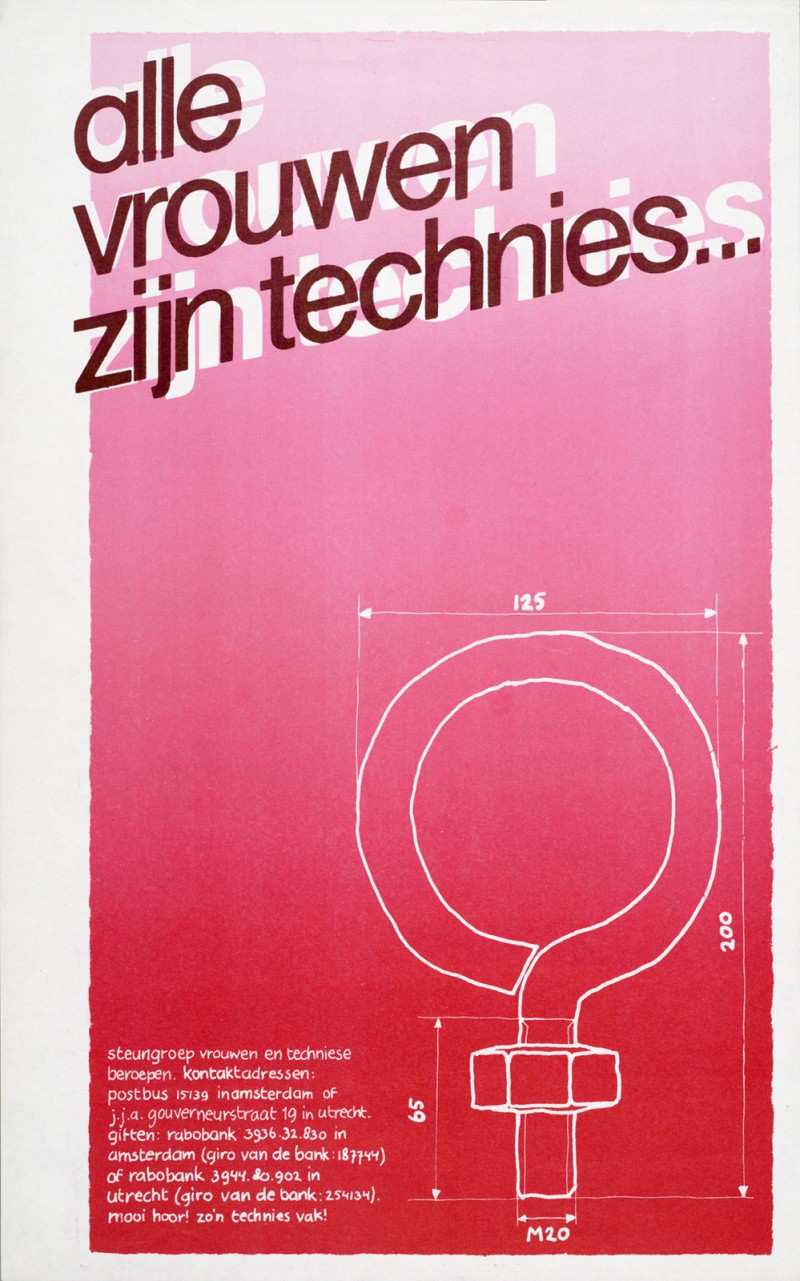

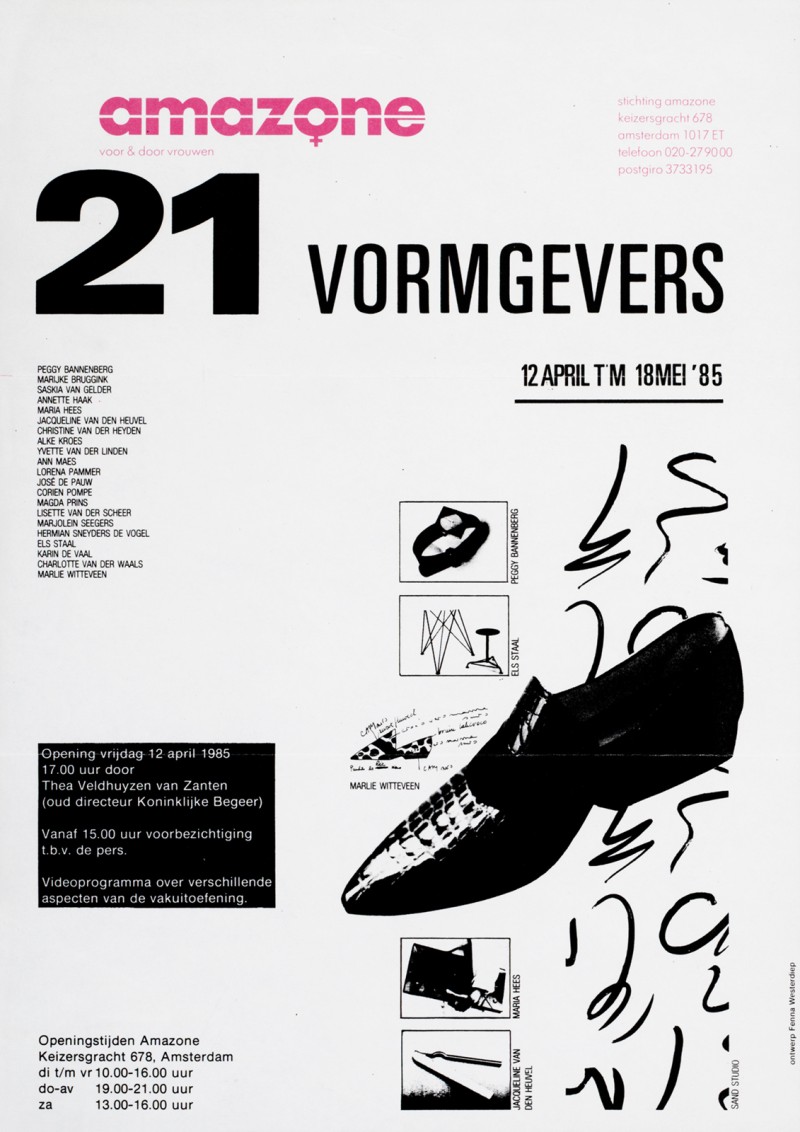

The book Posting brings together a selection of feminist posters from Dutch archives to reflect on posting as an activist strategy, holding the potential to create counter-publics to mainstream culture and to fight against the erasure, exoticization, or tokenism of bodies and experiences that deviate from normative preconceptions.

As is the case for many professions, in the history of Dutch graphic design the absence of women, non-binary, queer, Black designers is striking. This doesn’t only point back to systematic processes of exclusion in the first place, but also to the biases at play regarding whose work is remembered and archived. While efforts have been made to add forgotten names to the existing canon, the many posters, flyers and other printed matter shelved in queer and feminist archives remind us to question the notion of single authorship altogether and instead study graphic design as a decisively collaborative and transdisciplinary practice. Especially for community-led and volunteer-based projects, but also for individual expressions in a feminist spirit, it’s less of a concern who is the designer or creator, or what the medium is—a printed poster or book, a photo, video or text uploaded online, or a new platform—but rather what the act of making public entails, showing what one stands for, what is deemed important. Self-organized infrastructures for the creation, production, publication and distribution of contents shift into the center of attention, and here, we can learn from feminist initiatives in the ‘70s and ‘80s, who built collective and diverse graphic signatures, set up feminist printing collectives, publishing houses, and bookstores.

The posters featured in this book point to this rich landscape of feminist organizing, and were found at the International Institute of Social History and the International Archive for the Women’s Movement (IAV-Atria) in Amsterdam. They are framed by an introductory essay by Carolina Valente Pinto and an intergenerational roundtable conversation, in which posting is discussed as a way to (re)imagine and (re)design the social. The roundtable conversation, which was held as a multilingual space, has been translated into English and Dutch by Shira Wolfe.

- Book cover of Posting, eds. Carolina Valente Pinto, Tabea Nixdorff, published by Archival Textures, 2024.

- Pre-press work for a poster of Vrouwendrukkerij Las Muchachas [Women’s Press Las Muchachas], 198[?].

- Poster for women’s strike Vrouwen, leg het werk neer! [Women, Put Down Your Work!] by Vrouwenhuis Den Haag, 1980.

- Poster Alle vrouwen zijn technies [All Women are Technicians],Steungroep Vrouwen in Techniese Beroepen, 1978[?].

- Poster 21 vormgevers [21 Designers], exhibition by Stichting Amazone, voor en door vrouwen, 1985.

Source of images 2-5: Collection of the International Archive for the Women’s Movement, Amsterdam: Atria, Institute on Gender Equality and Women’s History; featured in the book Posting.

Red. Carolina Valente Pinto, Tabea Nixdorff

144 p, ills kleur, 16 × 23,7 cm, Nederlands/Engels

Verschenen in juni 2024

ISBN 97890-834194-4-2

Voor €18 te koop in jouw lokale boekenwinkel

In het boek Posting is een selectie feministische posters uit Nederlandse archieven verzameld ter reflectie op ‘posten’ als activistische strategie. Hiermee bestaat de mogelijkheid om een tegenbeweging te creëren die tegen de mainstream cultuur ingaat, en wordt gestreden tegen de uitwissing, het exotisme, of het enkel symbolische gebruik van lichamen en ervaringen die afwijken van normatieve vooroordelen.

Zoals bij zoveel vakgebieden het geval is, is het opvallend hoe weinig vrouwelijke, non-binaire, queer en Zwarte grafisch ontwerpers er in de geschiedenis van Nederlands grafisch ontwerp te vinden zijn. Ten eerste onderstreept dit niet alleen de systematische processen van exclusie, maar het wijst daarnaast ook op de vooroordelen die er bestaan als het gaat om wiens werk in de collectieve herinnering en in de archieven terechtkomt. Terwijl er inspanningen worden geleverd om vergeten namen op te nemen in de bestaande canon, herinneren de vele posters, flyers, en ander geprint materiaal in queer en feministische archieven ons eraan om het hele concept van de op zichzelf staande maker te bevragen, en om grafisch ontwerp in plaats daarvan te bestuderen als een praktijk die absoluut gaat over samenwerking en transdisciplinariteit. Vooral bij community- en vrijwilligersprojecten, maar ook bij individuele feministische uitingen, is het minder van belang wie de ontwerper of maker is, of wat het medium is — een gedrukte poster of boek, een foto, een online geüploade video of tekst, of een nieuw platform — maar gaat het om wat het betekent om iets publiek te maken, en om het laten zien waar je voor staat en wat je belangrijk vindt. Zelf-georganiseerde infrastructuren voor het creëren, produceren, publiceren en distribueren van content komen in het middelpunt te staan. Wat dit betreft kunnen we kennis opdoen van de feministische initiatieven uit de jaren 70 en 80, die collectieve en diverse grafische kenmerken ontwikkelden, en die feministische drukkerij collectieven, uitgeverijen en boekhandels oprichtten.

De posters in dit boek verwijzen naar dit rijkelijk gevulde landschap van feministisch organiseren, en werden gevonden in het Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis en in het Kennisinstituut voor Emancipatie en Vrouwengeschiedenis (IAV-Atria) in Amsterdam. Ze worden gepositioneerd door een inleidend artikel, geschreven door Carolina Valente Pinto, en met behulp van een intergenerationeel rondetafelgesprek waarin posten wordt besproken als een manier om de sociale sfeer te (her)ontwerpen en het ons (opnieuw) voor te stellen. Het rondetafelgesprek, dat werd georganiseerd als een meertalige ruimte, is vertaald naar het Engels en Nederlands door Shira Wolfe.

- Boekomslag van Posting, red. Carolina Valente Pinto, Tabea Nixdorff, gepubliceerd door Archival Textures, 2024.

- Drukwerk voor een poster van Vrouwendrukkerij Las Muchachas, 198[?].

- Affiche voor de landelijke vrouwenstaking Vrouwen, leg het werk neer! door Vrouwenhuis Den Haag, 1980.

- Affiche Alle vrouwen zijn technies, Steungroep Vrouwen in Techniese Beroepen, 1978[?].

- Affiche 21 vormgevers, tentoonstelling door Stichting Amazone, voor en door vrouwen, 1985.

Bron van afbeeldingen 2-5: Collectie van het Internationaal Archief voor de Vrouwenbeweging (IAV) in Atria, kennisinstituut voor emancipatie en vrouwengeschiedenis, Amsterdam; (her)gepubliceerd in het boek Posting.

Tuning in: Darimana?

Tineke E. Jansen

Eds. Tamara Hartman, Tabea Nixdorff, Tineke E. Jansen

120 p, ills bw, 16 × 23,7 cm, Dutch/English

Published June 2024

ISBN 978-90-834194-1-1

Available for €18 via your local bookstore

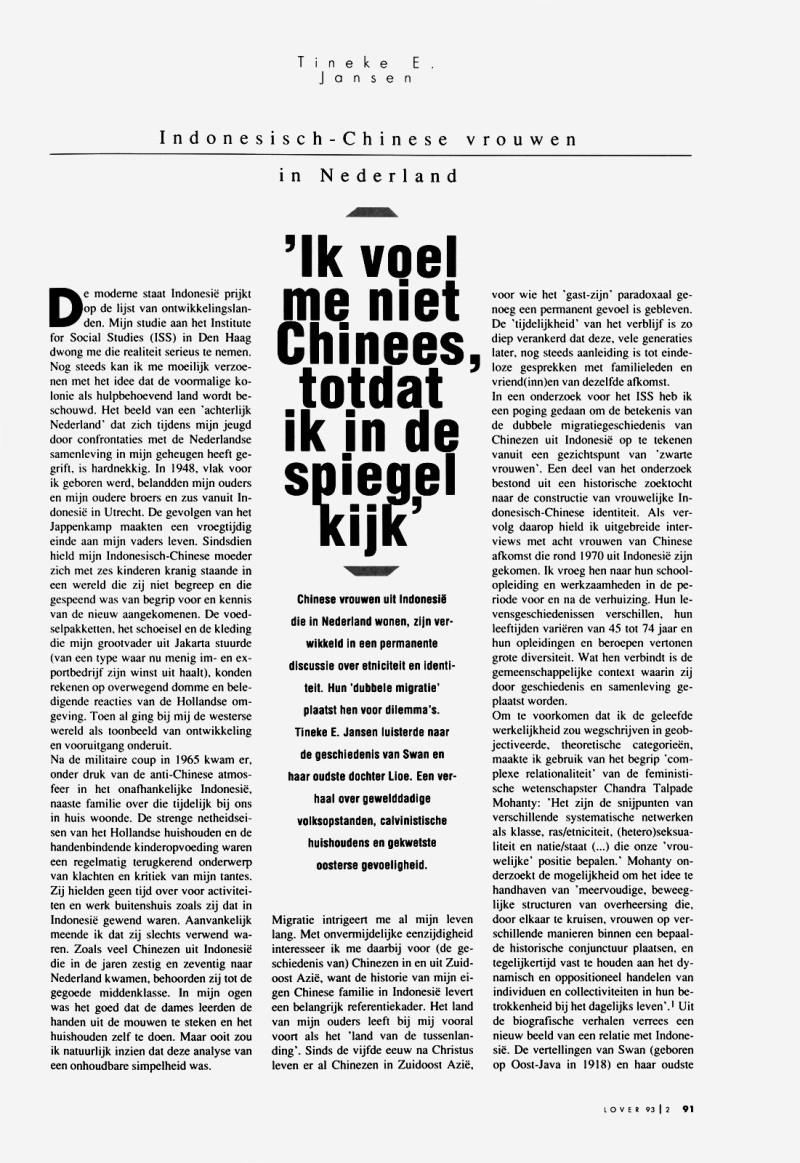

The book Tuning in: Darimana? revolves around a collection of 70 tapes with voices of Indonesian-Chinese women–an audio archive which finds its origins 40 years ago in Jakarta, Indonesia. When revisiting these tapes made by Tineke E. Jansen between 1980 and 1995, the act of attentive listening to the oral accounts of women’s experiences is central: Audio-recording allows “herstories” to be played back. It gives them that quasi-permanent quality which discerning listeners need, in order to fully grasp the meaning of voices, stories and emotions of the past. On Tineke’s audio recordings, Indonesian-Chinese women talk about their migration to the Netherlands in the ’50s and ’60s, about family, upbringing, and their experience with racism. How do we understand these recordings, which have remained hidden in the home archive until recently? Tamara Hartman speaks with Tineke, who shares her views on oral history, Black feminism in the Netherlands, and migration. Their conversation is framed by two archival texts which draw on the recorded stories: A reprint of an article published in feminist magazine Lover (1991) and a text that was once orally presented, but never published, titled Herlina Yang Tercinta (1994). Both texts derive from the collection of transcripts, notes, academic papers and pictures that are part of the archive. The book is a testament to one of the first attempts to tune in to Indonesian-Chinese women’s voices that rarely surface in public discourse.

- Book cover Tineke E. Jansen, Tuning In: Darimana?, eds. Tamara Hartman, Tabea Nixdorff, Tineke E. Jansen, published by Archival Textures, 2024.

- Indonesian-Chinese family members in their first home in the Netherlands in 1969, Source: Personal Archive Tineke E. Jansen.

- Cover of Lover, Literatuur Overzicht voor de Vrouwenbeweging, vol. 20, no. 2, 1993.

- Article “‘Ik voel me niet Chinees, totdat ik in de spiegel kijk.’ Indonesisch-Chinese vrouwen in Nederland.” [I don't feel Chinese until I look myself in the mirror. Indonesian-Chinese Women in the Netherlands] by Tineke E. Jansen, published in Lover, Literatuur Overzicht voor de Vrouwenbeweging, vol. 20, no. 2, 1993, pp. 90–97. Source: Collection of the International Archive for the Women’s Movement (IAV), Amsterdam: Atria, Institute on Gender Equality and Women’s History.

Tineke E. Jansen

Red. Tamara Hartman, Tabea Nixdorff, Tineke E. Jansen

120 p, ills zw, 16 × 23,7 cm, Nederlands/Engels

Verschenen in juni 2024

ISBN 978-90-834194-1-1

Voor €18 te koop in jouw lokale boekenwinkel

Het boek Tuning in: Darimana? draait om een collectie van 70 cassettebandjes met de stemmen van Indonesisch-Chinese vrouwen – een audioarchief met wortels in Jakarta, Indonesië, 40 jaar geleden. Bij het opnieuw beluisteren van deze bandjes, tussen 1980 en 1995 opgenomen door Tineke E. Jansen, staat het aandachtig luisteren naar de mondelinge getuigenissen van de ervaringen van vrouwen centraal: door audio-opnames kunnen 'herstories' worden teruggespoeld. Dit geeft geluid de quasi-permanente kwaliteit die kritische luisteraars nodig hebben om de betekenis van de stemmen, verhalen en emoties uit het verleden werkelijk te bevatten en recht te doen. In Tineke’s audio-opnames spreken Indonesisch-Chinese vrouwen over hoe het was om te migreren naar Nederland in de jaren 50 en 60, over familie, opvoeding, en hun ervaringen met racisme. Hoe begrijpen we deze opnames nu, die tot voor kort publiekelijk onbekend gebleven in het thuisarchief lagen? Tamara Hartman gaat in gesprek met Tineke, die haar kijk geeft op mondelinge geschiedenis, Zwart feminisme in Nederland, en migratie. Hun gesprek wordt gepositioneerd door twee teksten uit het archief die voortbouwen op de opgenomen verhalen: een herdruk van een artikel dat gepubliceerd werd in het feministische tijdschrift Lover (1991), en de tekst Herlina Yang Tercinta (1994), die ooit mondeling is gepresenteerd, maar nooit is gepubliceerd. Beide teksten komen uit de verzameling transcripties, notities, academische papers, en foto’s die behoren tot het archief. Dit boek laat een van de eerste ondernemingen zien die intense aandacht vragen voor het luisteren naar Indonesisch-Chinese vrouwen, wier stemmen zelden in het publieke discours gehoord worden.

- Boekomslag Tineke E. Jansen, Tuning In: Darimana?, red. Tamara Hartman, Tabea Nixdorff, Tineke E. Jansen, gepubliceerd door Archival Textures, 2024.

- Indonesisch-Chinese familieleden in hun eerste huis in Nederland in 1969, Bron: Persoonlijk Archief Tineke E. Jansen.

- Omslag van Lover, Literatuur Overzicht voor de Vrouwenbeweging, jg. 20, nr. 2, 1993.

- Artikel “‘Ik voel me niet Chinees, totdat ik in de spiegel kijk.’ Indonesisch-Chinese vrouwen in Nederland.” door Tineke E. Jansen, gepubliceerd in Lover, Literatuur Overzicht voor de Vrouwenbeweging, jg. 20, nr. 2, 1993, pp. 90–97. Bron: Collectie van het Internationaal Archief voor de Vrouwenbeweging (IAV) in Atria, kennisinstituut voor emancipatie en vrouwengeschiedenis, Amsterdam.

Republishing: Umoja Zwarte Vrouwenkrant

Eds. Tamara Hartman, Ans Sarianamual, Mirelle van Tulder, Tabea Nixdorff

580 p, ills bw, 20 × 28 cm, Dutch/English

Published October 2024

ISBN 978-90-834194-0-4

Available for €35 via your local bookstore

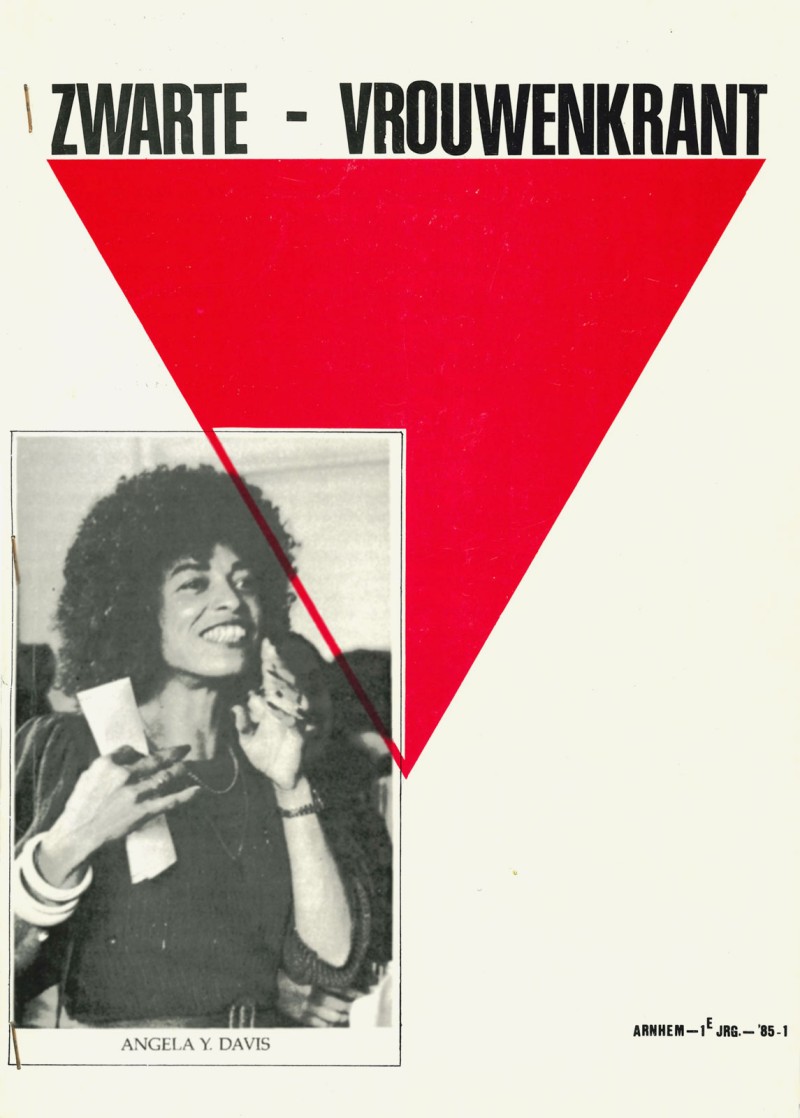

The book Republishing: Umoja Zwarte Vrouwenkrant makes a groundbreaking yet vastly unacknowledged grassroots magazine from Arnhem accessible as a source to enrich the still underexposed legacies of Black feminists in the Netherlands.

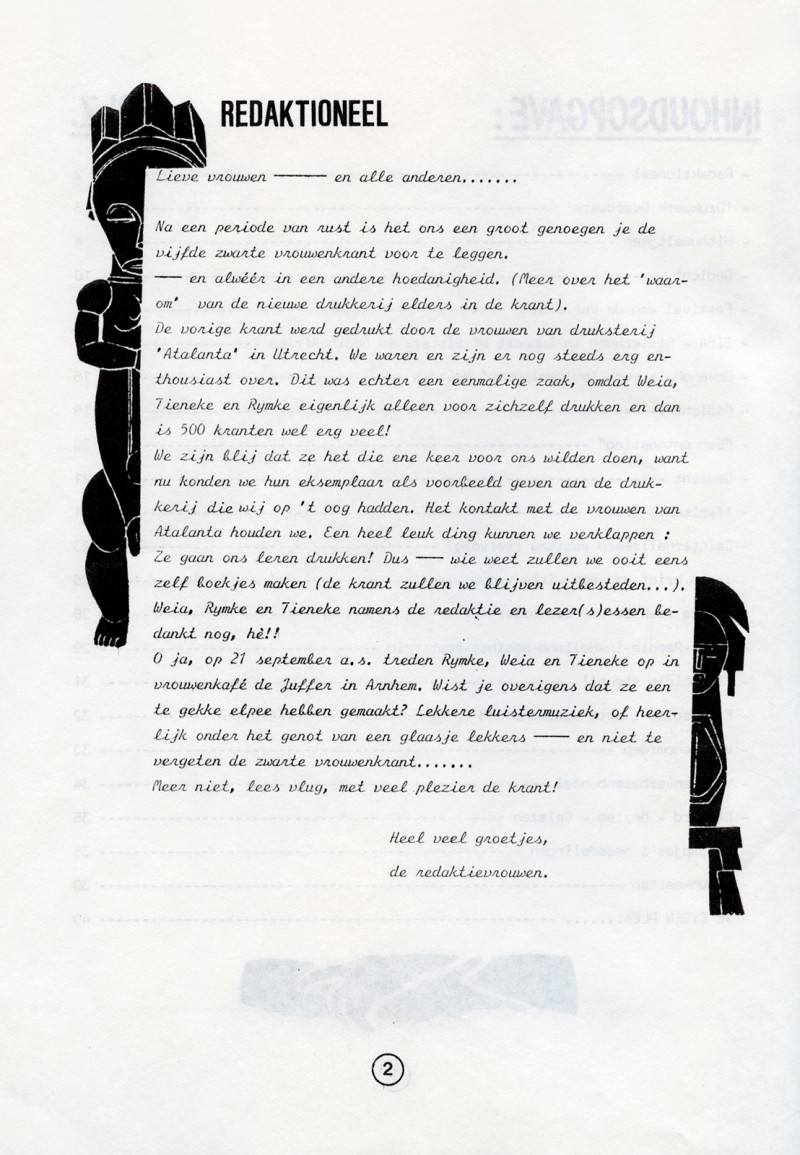

It all started in December 1984, when Ans Sarianamual made a promise to Audre Lorde to start a magazine for Black women in the Netherlands. Together with a group of Black women organized as the foundation ‘Zwarte Vrouwen & Racisme’ Arnhem, the first issue of Umoja Zwarte Vrouwenkrant was published only one month later. As aptly put in the editorial: “So much has already been written about us, which means our time was mostly spent on reacting to pieces written about us by white women. [...] Let’s start speaking ourselves now!” The magazine (1985–1986) was unique for its time because of its radically intersectional approach, and the establishment of “black” as a political term in order to unite and strengthen all women who were labeled as “the Other” in the Netherlands and beyond. The magazine built on transnational friendships, featuring writings by and about Black women's groups in the U.S., England and South Africa. Besides writing on subjects such as racism, (employment) discrimination and decolonization, Umoja Zwarte Vrouwenkrant published poems, interviews with Dutch Black writers, event announcements and letter submissions in which Black women shared their experiences of racism and discrimination in the Netherlands.

Umoja Zwarte Vrouwenkrant is a revolutionary magazine whose legacy has gotten no recognition. This book aims to bring about change here, and thereby historicize the complete set of magazines, contextualized through an introductory essay by Tamara Hartman and archival findings from Ans Sarianamual’s personal archive, edited by Mirelle van Tulder. Republishing these magazines also means to think of publications as low-threshold archives which help make Black feminist knowledges of the Netherlands accessible outside of archival institutions.

- Book cover of Republishing: Umoja Zwarte Vrouwenkrant, eds. Tamara Hartman, Ans Sarianamual, Mirelle van Tulder, Tabea Nixdorff, published by Archival Textures, 2024

- Cover of the original Umoja Zwarte Vrouwenkrant, vol. 1, no. 1, January 1985, published by Stichting ‘Zwarte Vrouwen & Racisme’ Arnhem.

- Editorial Note Lieve vrouwen… en alle anderen, published in Umoja Zwarte Vrouwenkrant, vol. 1, no. 4, 1985, p. 2. Arnhem: Stichting ‘Zwarte Vrouwen & Racisme’ Arnhem.

- Back cover of Umoja Zwarte Vrouwenkrant, vol. 1, no. 1, 1985, published by Stichting ‘Zwarte Vrouwen & Racisme’ Arnhem.

Source of images 2-4: Personal Archive Ans Sarianamual

Red. Tamara Hartman, Ans Sarianamual, Mirelle van Tulder, Tabea Nixdorff

580 p, ills z/w, 20 × 28 cm, Nederlands/Engels

Verschenen in oktober 2024

ISBN 978-90-834194-0-4

Voor €35 te koop in jouw lokale boekenwinkel

Het boek Republishing: Umoja Zwarte Vrouwenkrant maakt een baanbrekend, maar totaal onerkend grassroots tijdschrift uit Arnhem toegankelijk als een bron om te leren van en over de nog steeds onderbelichte nalatenschappen van Zwarte feministen in Nederland.

Het begon allemaal in december 1984, toen Ans Sarianamual een belofte deed aan Audre Lorde om een tijdschrift op te zetten voor Zwarte vrouwen in Nederland. Samen met een groep Zwarte vrouwen, die zich organiseerden als de stichting ‘Zwarte Vrouwen & Racisme’ Arnhem, werd het eerste nummer van Umoja Zwarte Vrouwenkrant al een maand later gepubliceerd. Zoals ze treffend schreven in het redactioneel: “Er is al zoveel óver ons geschreven. Onze tijd ging dan ook vooral zitten in het reageren op stukken geschreven door witte vrouwen over ons. [...] Laten we nu zelf spreken!” Het tijdschrift (1985 – 1986) was uniek in die tijd vanwege de radicaal intersectionele aanpak, en de invoering van ‘Zwart’ als politieke term, met het doel om alle vrouwen in en buiten Nederland die als ‘de Ander’ gelabeld werden bij elkaar te brengen en kracht te geven. Het tijdschrift bouwde voort op transnationale vriendschappen en publiceerde stukken van en over Zwarte vrouwengroepen in de Verenigde Staten, Engeland en Zuid-Afrika. Naast het schrijven over onderwerpen als racisme, (arbeids)discriminatie en dekolonisatie, publiceerde Umoja Zwarte Vrouwenkrant gedichten, interviews met Zwarte Nederlandse schrijvers, aankondigingen van evenementen en briefinzendingen waarin Zwarte vrouwen hun ervaringen met racisme en discriminatie in Nederland deelden.

Umoja Zwarte Vrouwenkrant is een revolutionair tijdschrift met een nalatenschap die geen erkenning heeft gekregen. Dit boek heeft als doel om hier verandering in te brengen en daarmee de volledige reeks tijdschriften te historiseren. Er wordt context gegeven door een inleidend essay geschreven door Tamara Hartman en door vondsten uit het persoonlijke archief van Ans Sarianamual, samengesteld door Mirelle van Tulder. Het herpubliceren van deze tijdschriften betekent ook dat we over publicaties gaan beschouwen als laagdrempelige archieven die een bijdrage leveren aan de toegankelijkheid van Zwarte feministische kennis in Nederland, buiten de archiefinstellingen.

- Boekomslag van Republishing: Umoja Zwarte Vrouwenkrant, red. Tamara Hartman, Ans Sarianamual, Mirelle van Tulder, Tabea Nixdorff, gepubliceerd door Archival Textures, 2024

- Omslag van Umoja Zwarte Vrouwenkrant, jg 1, nr. 1, 1985, gepubliceerd door Stichting ‘Zwarte Vrouwen & Racisme’ Arnhem.

- Noot van de redactie Lieve vrouwen… en alle anderen, gepubliceer in Umoja Zwarte Vrouwenkrant, jg. 1, nr. 4, 1985, p. 2. Arnhem: Stichting ‘Zwarte Vrouwen & Racisme’ Arnhem.

- Omslag achterkant van Umoja Zwarte Vrouwenkrant, jg 1, nr. 1, 1985, gepubliceerd door Stichting ‘Zwarte Vrouwen & Racisme’ Arnhem.

Bron van afbeeldingen 2-4: Persoonlijk archief Ans Sarianamual

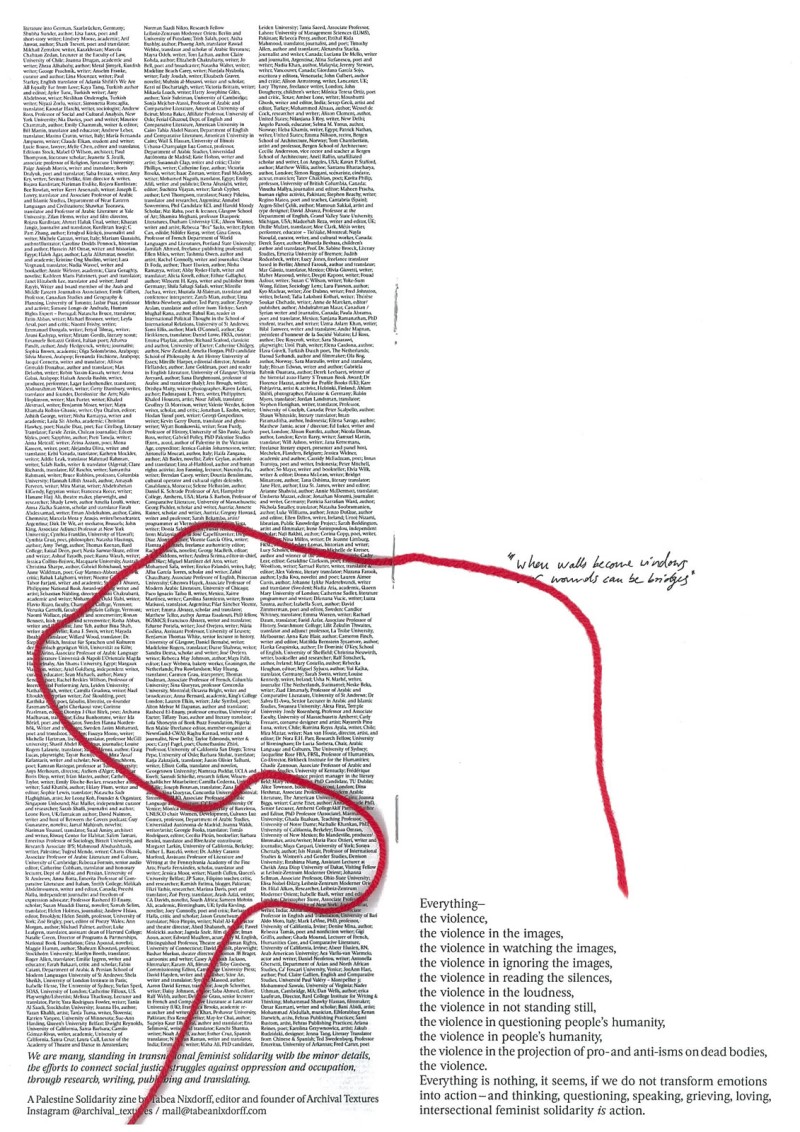

A Palestine Solidarity Zine #2

Eds. Tamara Hartman, Tabea Nixdorff

44 p., ills bw, 10,5 × 29,7 cm, English, March 2025

Available in selected bookshops for donation*

With contributions by: Mahmud Abu-Odeh, Gráinnemir Amir Abualrob, Anita Di Bianco, Flip Driest, Moosje M. Goosen, Tamara Hartman, Canan Marasligil, Tabea Nixdorff, Shira Wolfe

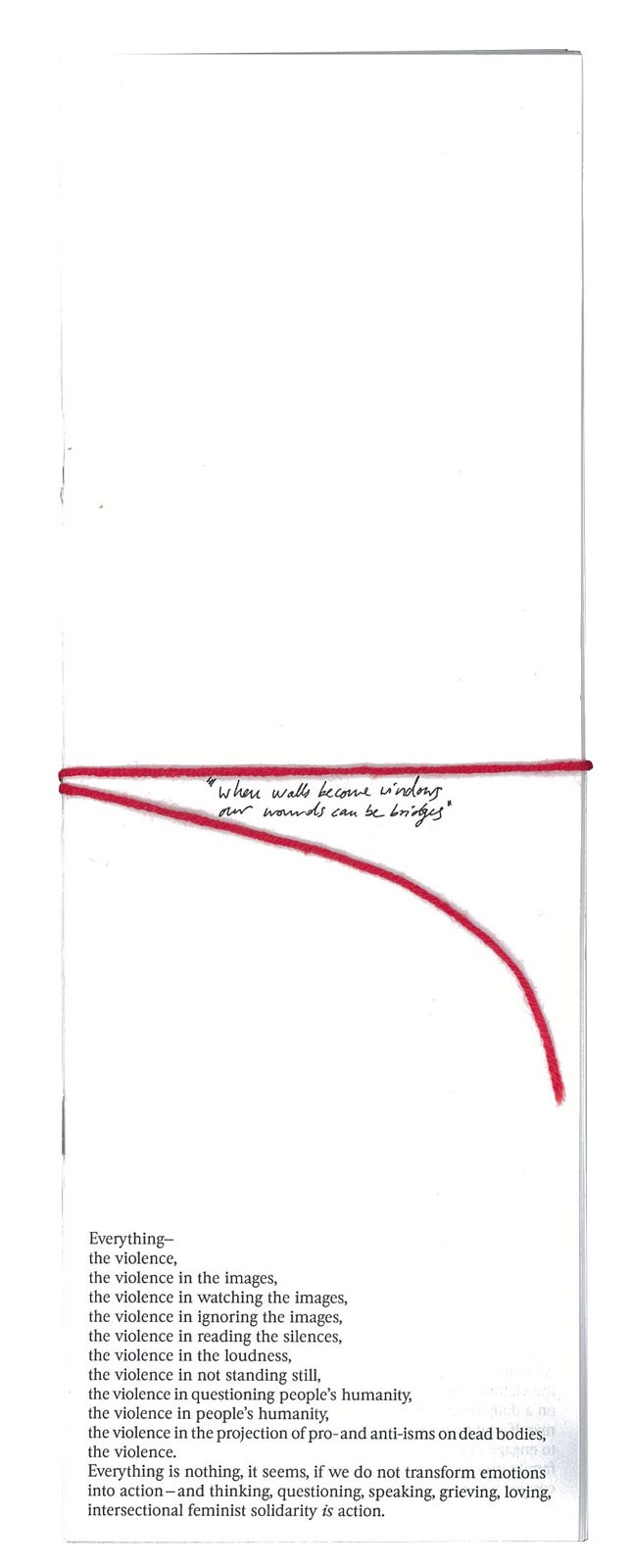

Seven written contributions form this second issue of A Palestine Solidarity Zine: from conversations on silence and censoring of Palestine solidarity in Germany to the question of impunity in relation to IDF-soldiers vacationing in India, to Palestinian poetry in dialogue.

Even if Israel’s genocidal intentions were clearly legible from zionist statements and actions since well before the Nakba started, the scale and extent of the dehumanization and the destruction of Palestinian lives and livelihoods which we have been witnessing for over a year now can hardly be fathomed. The urgent question remains every day: how can we contribute to refuse the normalization of this ongoing genocide?

With our practices being rooted in archives and books, it means never losing sight of our work’s underlying claim that researching histories of resisting oppression should fuel our current practices of solidarity.

The making of this zine is also inspired by the conviction that we have to build our own archives, as we see the enormous efforts undertaken by governments and lobby groups trying to censor, criminalize and repress the circulation of knowledges, stories and experiences that dismantle zionism as one of many ideologies that in fact make no one safer, but instead expose the cruel adaptiveness of colonialism to specific imperial aspirations.

Those who attempt to silence people forget that resistance always survives. Embodied. In songs. In stories. In the soil. In friendships.

*One third of collected donations cover production costs, two thirds of the proceeds will be donated to grassroots initiatives that use publishing, research and archiving as their tools towards liberation, such as The Hind Rajab Foundation, an initiative that focuses on countering Israeli impunity through legal action, awareness campaigns and commemoration of all the people that we have lost; Accountability Archive, an initiative that holds records of journalists, politicians, and public figures endorsing ethnic cleansing of Gaza and defaming pro-Palestinian activists; Archive of Silence, a crowdsourced archive documenting silenced voices in Germany, in order to chronicle the alarming waves of erasure and violence directed at Palestinian advocacy in Germany.

A Palestine Solidarity Zine #1

Ed. Tabea Nixdorff

40 p, ills bw, 10,5 × 29,7 cm, English

November 2023 (out of print)

As founder and editor of the publication series Archival Textures, I feel grateful to work together with a close network of co-editors, translators, writers and archivists, without whose collaborative efforts the upcoming titles would not materialize. Archival Textures was founded with the intention to find and (re)distribute writings of the past that can inform our current vocabularies of solidarity and resistance against normative perspectives on our bodies, desires, and forms of cohabitation. Taking this intention seriously also means to allow the work to be disrupted by what deeply disturbs and scares us in the present moment.

How can we practice solidarity right now, one that is neither failing the urgency of stopping the Nakba, including the genocide in Gaza unfolding on our screens, while also holding space for the feminist intersectional struggles we draw hope from, which includes the search for a just future for all in Palestine/Israel? This zine is trying just that, with the means closest to my practice: artistic publishing, literature, research. I pulled together fragments from the digital phone “archive” over these past weeks, when probably many of us took screenshots of words that resonated in this distressing moment. I invited Archival Textures contributors to share from their collections of screenshots, links or personal notes and pieces of writing.

Special thanks, for invaluable ongoing conversations, to Tamara Hartman, Anita Di Bianco, and Shira Wolfe, also for so generously sharing a piece of writing, as well as to Setareh Noorani, Canan Marasligil, Anne Krul, Ans Sarianamual and Delany Boutkan for sharing links, text and image fragments.

(Tabea Nixdorff, November 2023)

Donations for the zine were forwarded to these three initiatives: Women’s Centre for Legal Aid and Counselling (WCLAC), The Fire These Times, and Standing Together.